The effect of auditory distraction on cognitive flexibility

Abstract

This study investigated the effect of auditory distraction on cognitive flexibility by analyzing data collected on 72 STA490 students who took the Stroop test while listening to music. The students also took the test without listening to music as a control. Several other variables were recorded as potential confounders which may further explain the relationship between cognitive flexibility and auditory distraction. Two linear mixed models were used in the analysis with a measurement for cognitive flexibility as the response variable and auditory distraction level as the main independent variable of interest. The first model used only auditory distraction as a covariate while the second model added the order of auditory distraction and the device type used for the Stroop test. Both models reached the same conclusion that auditory distraction affects cognitive flexibility. Furthermore, it appears that cognitive flexibility improves when listening to music.

Introduction

Cognitive flexibility is measured by how quickly your brain can switch from thinking about one concept to another. This is a particularly important trait in certain professions that require multi-tasking and it is especially important for university students, as cognitive flexibility could be connected to problem-solving and memory retention. One way to measure cognitive flexibility is by having participants take a test that measures the Stroop Effect, which records the time that it takes to identify colours of the text where the colour and text are not matching. For instance, the display might show a blue colour of the word “green” and the subject must identify the colour as blue to obtain the correct answer. The time taken to complete five correct runs are recorded for text in the form of symbols (i.e. Stroop is off), and for text that represent a non-corresponding colour (i.e. Stroop is on). The response variable that measures cognitive flexibility is the difference between the two time results. A lower time difference means greater cognitive flexibility.

The goal of this study is to determine whether auditory distraction affects cognitive flexibility. In order to achieve this aim, participants took the Stroop test while listening to two different types of music (classical and lyrical) and without listening to any music as a control. Several other variables mentioned in the Methods section were also recorded as potential confounding variables. The variable which stood out as a potential confounder is the order of auditory distraction used for the Stroop test. After the models were fit, we arrived at a conclusion that cognitive flexibility is improved by auditory distraction. With these results, we may recommend that students can listen to music while studying or working on their assignments.

In the Methods section, two linear mixed models are discussed. The first model is a very simple model that takes auditory distraction as the only independent variable. The second model builds on the first model by adding two covariates: order of auditory distraction and device used for the Stroop test. In the Results section, summary tables and the two model outputs are provided. The most important values to look at are the p-values for auditory distraction which are significant (i.e. smaller than 0.05) in both models. With significant p-values for distraction we arrived at the conclusion that auditory distraction has a significant effect on the response variable. Finally, the models and results are further interpreted in the Discussion section and we also discuss the study design.

Methods

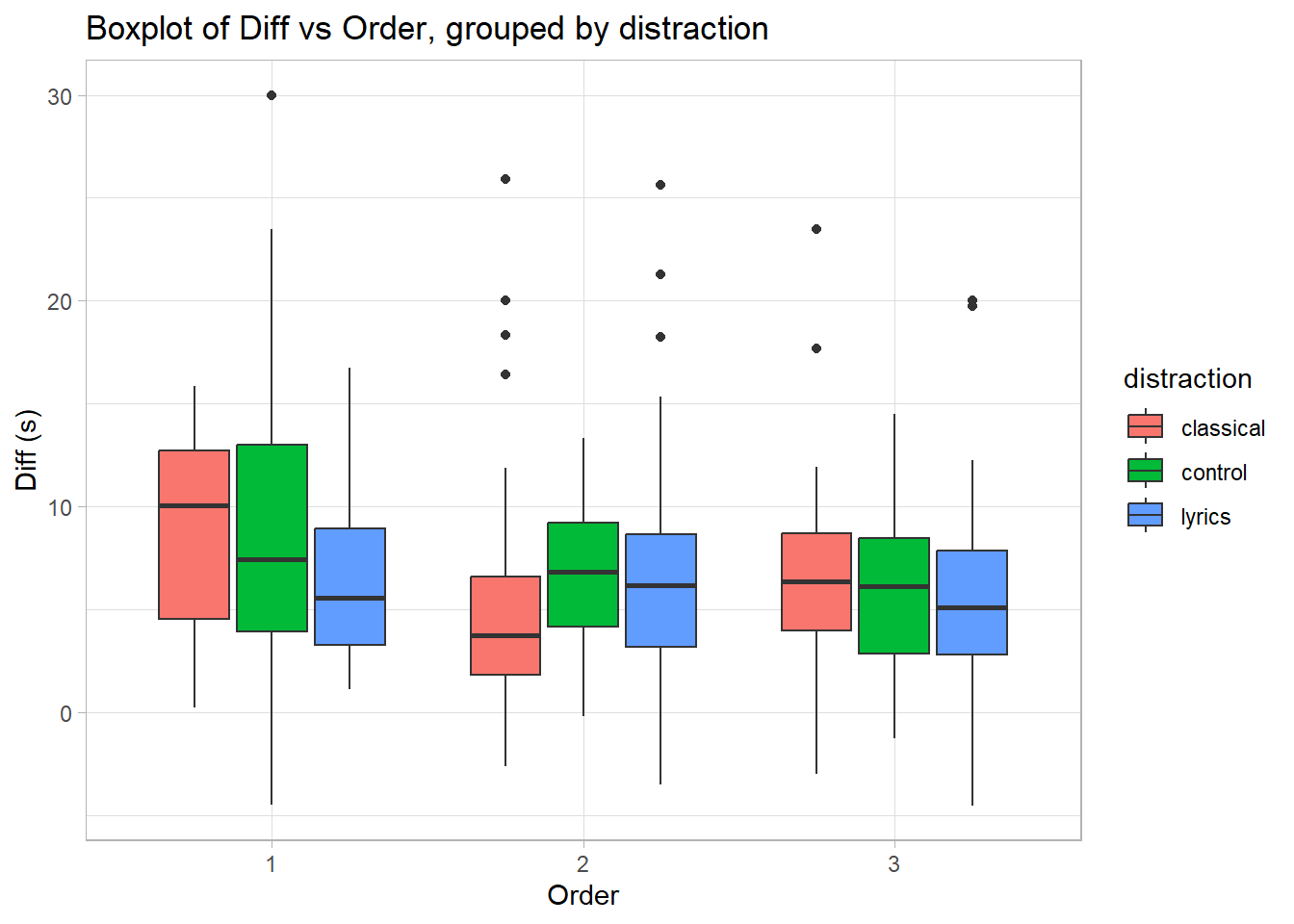

The dataset was taken from a survey that was given to 72 students in STA490 to fill out once they completed the Stroop test by EncephalApp on a mobile device during the period from September 12 to September 17 2019. The app measures the time taken to complete the test after five correct trials in two instances: offtime (i.e. Stroop is off) and ontime (i.e. Stroop is on). When Stroop is on, the displayed text will contain words that do not correspond to their correct colour, whereas when Stroop is off the displayed text are coloured symbols such as the number sign (‘#’). The response variable which is used to measure cognitive flexibility is diff, the difference between ontime and offtime. EncephalApp also collected two variables: runsoff and runson which are the number of trials required to get five correct runs in both the “off” and “on” states respectively. The main independent variable that we are investigating is distraction, which represents three different levels of auditory distraction: quiet (control), music with lyrics, classical music. The students were asked to randomize the order in which these three distractions were used for the Stroop test. Unfortunately, some students failed to follow this instruction as Figure 1 shows that the mean difference (diff) decreases as the order in which the distractions were used increases. As a result order is likely a confounding variable which should be included in at least one of our models. Students were also asked to take the test in a quiet environment so that there would be no external distractions. In addition, other potential confounding variables were collected for the dataset, including colour blindness, years studied at an English institution, video games, device type, type of headphones, hours of sleep the night before, time of day. Finally, each student is distinguished by an identifier, id.

Figure 1: Boxplot of Difference vs Order, grouped by distraction level

Model 1

The first model used to investigate the research question is a linear mixed model with ontime minus offtime as the response variable (diff), auditory distraction level as a covariate and student id as a random effect:

\[

\text{diff}_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \text{distraction}_{ij} + b_i + e_{ij}

\]

where \(b_i\) is the random effect for id, and \(e_{ij}\) are the error terms.

The reason this model was chosen is due to the fact that we are particularly interested in how auditory distraction affects cognitive flexibility so including other covariates may not be necessary. This is the simplest model that we can use to answer the research question. In addition, the way in which the data was collected meant that each student had three dependent observations - one for each level of auditory distraction, thus it is necessary to use id as a random effect in the model. The model assumptions of linearity, constant variance and normality of the residuals were checked.

Model 2

The second model adds two additional covariates to Model 1, the order in which the distractions were used and type of device used for the Stroop test. An interaction term between distraction and order is also included. The response variable and random effects remain the same, and the model can be written as:

\[ \text{diff}_{ij} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \text{distraction}_{ij} + \beta_2 \cdot \text{order}_{ij} + \beta_3 \cdot \text{distraction}_{ij}:\text{order}_{ij} + \beta_4 \cdot \text{device} + b_i + e_{ij} \]

This model looks at how order and device can affect the response as confounding variables. They may decrease the significance of distraction if they play an important role in affecting cognitive flexibility. The model assumptions of linearity, constant variance and normality of the residuals were checked.

Results

Model 1

In Table 1, there is a noticeable difference in the means of control and the other two groups. The control category represents students taking the Stroop test in a quiet environment with no music, so we may expect to see that the control group should perform better than the other two groups by obtaining a smaller difference, but that is not the case here. This can possibly be explained by adding a confounding variable to the model such as order, which we will do in Model 2. From the model output in Table 2, distraction has a p-value of 0.034 which is smaller than the significance level of 0.05. This indicates that auditory distraction has an affect on cognitive flexibility. More specifically, listening to music with lyrics or classical music actually improves cognitive flexibility based on these results.

| distraction | mean.ontime.minus.offtime |

|---|---|

| classical | 6.41 |

| control | 8.21 |

| lyrics | 6.61 |

| numDF | denDF | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1 | 142 | 156.887 | 0.000 |

| distraction | 2 | 142 | 3.462 | 0.034 |

Model 2

Starting with Table 3, we can see that on average students perform worse on the first attempt at the Stroop Test. Table 4 builds on this by showing the breakdown of the mean differences and counts for each auditory distraction by order. Most noticeably, 56 out of 72 students had the quiet condition (control) as their first auditory distraction, which greatly affected the results in Table 1 and helps explain why the control group performed worse than the classical and lyrics groups. However, control performed worse than classical for orders 2 and 3, and worse than lyrics for orders 1 and 3. Despite accounting for order, the control group did not perform well overall which may be due to the uneven counts across each group. Next, we look at Table 5 which shows us that android phone users performed worse than iPhone and iPad users so device may be a confounding variable.

From the model output in Table 6, distraction has a p-value of 0.041 which is smaller than the significance level of 0.05. This indicates that auditory distraction has an affect on cognitive flexibility even after we account for order and device. It is interesting to note that order has a p-value of 0.058 which is close to but not below the threshold of 0.05, while device has a p-value of 0.049 which is slightly below the significance level. The interaction term distraction:order is not significant as the p-value is 0.863. This means that the order of distraction used for the Stroop test does not quite have a significant effect while the device used for the Stroop test has a somewhat significant effect on cognitive flexibility. With this model we reach the same conclusion as in Model 1 that auditory distraction affects cognitive flexibility and surprisingly shows an improvement in cognitive flexibility.

| order | mean.ontime.minus.offtime |

|---|---|

| 1 | 8.42 |

| 2 | 6.64 |

| 3 | 6.16 |

| distraction | order | mean.ontime.minus.offtime | count |

|---|---|---|---|

| classical | 1 | 8.74 | 6 |

| classical | 2 | 6.01 | 28 |

| classical | 3 | 6.33 | 38 |

| control | 1 | 8.70 | 56 |

| control | 2 | 6.67 | 7 |

| control | 3 | 6.40 | 9 |

| lyrics | 1 | 6.72 | 10 |

| lyrics | 2 | 7.11 | 37 |

| lyrics | 3 | 5.82 | 25 |

| device | mean.ontime.minus.offtime |

|---|---|

| Android phone | 10.07 |

| iPad tablet | 6.42 |

| iPhone / iPod | 6.50 |

| numDF | denDF | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1 | 139 | 161.493 | 0.000 |

| distraction | 2 | 139 | 3.266 | 0.041 |

| order | 1 | 139 | 3.660 | 0.058 |

| device | 2 | 69 | 3.153 | 0.049 |

| distraction:order | 2 | 139 | 0.148 | 0.863 |

Discussion

In both linear mixed models, the p-values for distraction are smaller than than the significance level of 0.05. The second model includes the additional covariates order and device which were potential confounding variables, however we reached the same conclusion. Listening to music with lyrics or classical music has an effect on diff - the difference between ontime and offtime, when compared to taking the test in silence. In order words, auditory distraction improves cognitive flexibility. This holds true even once we account for the order in which the distraction levels were used and the type of device used for the Stroop test.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of a large sample size. The dataset only contains information for 72 subjects, all of whom are students in STA490 and are in their fourth year of university studying statistics. Since the sample size is rather small and it contains students of a very niche demographic it is difficult to generalize our results to the general population. Another problem was that many students appeared to not follow instructions, by not randomizing the order of auditory distraction level they used for the Stroop test. 56 out of 72 students had control as their first auditory distraction and the data showed us that the control group performed worse than classical and lyrics even when accounting for order. But the number of students who had control as orders 2 and 3 were very small (7 and 9 respectively). This led to the unintuitive conclusion that auditory distraction improves cognitive flexibility. However, if we had equal sized groups or many more data points our conclusion may have been the opposite. Specifically, it may be more sensible that auditory distraction worsens cognitive flexibility despite what this study shows.

From this study we were able to show that auditory distraction not only affects cognitive flexibility but improves cognitive flexibility for University of Toronto students taking STA490. The results can somewhat be generalized to other students of a similar demographic. For instance, we can recommend that university students should listen to music while working on tasks such as assignments and readings to improve their cognitive flexibility. Unfortunately we can not generalize these results to a broader population, so the results of this study are not particularly useful to other age groups and people in various professions that may want to know whether or not they should listen to music while doing particular work.

Appendix

Code

library(tidyverse)

library(readr)

library(knitr)

library(nlme)

# Load data and rename variables

data <- read_csv("./files/cognitive.csv")

names(data) <- c("id", "cblind", "english", "vgames", "device", "headphones",

"alllevels", "distraction", "sleep", "start", "offtime",

"ontime", "runsoff", "runson", "diff", "order")

# Boxplot

ggplot(data=data,aes(x=factor(order),y=diff, fill=distraction)) +

geom_boxplot() +

theme_light() +

labs(title="Boxplot of Diff vs Order, grouped by distraction",

x="Order",

y="Diff (s)")

# Table 1: Auditory distraction means

data %>%

group_by(distraction) %>%

summarise(mean.ontime.minus.offtime = round(mean(diff), 2)) %>%

kable(caption = "Auditory distraction means")

# Linear Mixed Model 1

simple.model <- lme(diff ~ distraction, random=~1|id, method="REML", data=data)

# Table 2: Linear Mixed Model 1

kable(round(anova(simple.model), 3), caption = "Linear Mixed Model 1")

# Linear Mixed Model 2

model_dv <- lme(diff ~ distraction*order + device, random=~1|id,

weights=varIdent(form=~1|order), method="REML", data=data)

# Table 3: Order means

data %>%

group_by(order) %>%

summarise(mean.ontime.minus.offtime = round(mean(diff), 2)) %>%

kable(caption = "Order means")

# Table 4: Distraction by Order means

data %>%

group_by(distraction, order) %>%

summarise(mean.ontime.minus.offtime = round(mean(diff), 2), count = n()) %>%

kable(caption = "Distraction by Order means")

# Table 5: Device type means

data %>%

group_by(device) %>%

summarise(mean.ontime.minus.offtime = round(mean(diff), 2)) %>%

kable(caption = "Device type means")

# Table 6: Linear Mixed Model 2

kable(round(anova(model_dv), 3), caption = "Linear Mixed Model 2")